Perhaps one of the longest held beliefs about ekphrastic poetry is that it is preoccupied with the stillness of the image. This bifurcation between frozen, silent images in visual art and active, speaking subjects in poetry has been the axel upon which most of our critical attention to the genre has turned. But what if we could show that stillness was “not” the most central concept to ekphrastic verse? What if, perhaps, it was some other trope that we have overlooked because we as readers are captivated by that alluring binary? This is one line of questioning that I have been pursuing in my own research, and I’m going about asking this question in very different ways: using the “close reading” of conventional literary study and the more “distant” reading of computational text analysis. The text analysis has been slow, because unlike many other kinds of data analysis projects, I do not have huge datasets to work with. If you work in the digital humanities, one of the underlying conversations has been about how much natural language data we have. From Google’ Books’ digitized corpus to the Hathi Trust to LION, there are thousands of texts available… but not if you’re working on 20th century poetry. Here’s where things get much murkier. Large corpuses of 20th century poetry are protected under copyright law. So, regardless of the fact that I have no desire to republish the texts in whole (or even in substantial part) the largest drag on my research is that a single dissertating student has almost no resources to generate the substantively-sized data sets that someone would need in order to really study ekphrasis in a more reliably comprehensive way.

And yet, that’s exactly what I want to do.

As a first step, I have taken time to digitize (only for data purposes) one of the canonical anthologies of ekphrastic verse: The Gazer’s Spirit edited by John Hollander. Hollander’s text provides a history and taxonomy of ekphrasis, which has created the foundation for most scholarly work on the subject since the 1980s. In his introduction, Hollander defines ekphrasis as poems to, for, and about the visual arts. He traces its history from the earliest records of Greek rhetoric through its first widely-recognized use in Homer’s Illiad to its various iterations: conversations with artists, gallery walks, notional (about imaginary works of art), actual (about works of art we can still see), unassessable (poems about works of art that no longer exist), architectural ekphrasis, photographic ekphrasis, etc. Hollander’s book provided readers with insights into the tropes, agendas, and dilemmas and accompanied that introduction with what he called a “gallery” of ekphrastic poems to, for, and about actual works of visual art. It is considered, therefore, and ekphrastic primer.

Hollander’s collection, then, seemed like a reasonable place to start with text analysis. The gallery features 48 poems accompanied by either black and white or full color pictures of the works of art each poem addresses. Hollander follows each poem up with explication and analysis, and occasionally with additional poems that might help to shed historical light on the main poem for that entry. I have only reproduced the “gallery” poems, and not those Hollander refers to in part or full.

My question, then, going into this small experiment in text analysis has been this: Can we tell through simple text analysis such as word frequency, phrase frequency, and word proximity if Hollander’s claims about the usual tropes of ekphrasis are true? This is, obviously, a flawed question, because text analysis tools are not able to read or to understand figurative language, which is the means and the material of ekphastic verse; however, Hollander makes claims that have shaped the scope of scholarly research about ekphrasis since the 1980s, and those claims depend much of the time on the repetition of phrases and words.

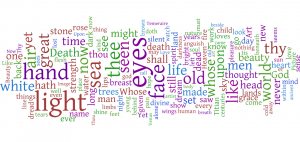

Several freely available tools exist for creating text frequency visualizations. These are called word cloud or text cloud generators. The tools are primarily useful for aesthetic purposes; however, their is a usefulness to their impressionism. As pictures of relative prominence, these images can help to shift our sense of what some of the most common topics, phrases, and words are in data set. The first tool I’ve used is derived from Jonathan Feinberg’s wordle.net. More information about the tool, now housed on IBM’s Many Eyes site can be found here.